(American Mink)

Either of two weasel-like species of the genus Mustela (M. vison [see photograph], New World mink, of forests in North America, and M. lutreola, Old World mink, of Eurasia) are of the weasel family, Mustelidae.The mink was introduced into England from the United States in 1929 to be bred for it's fur. But numbers escaped, for various reasons, and they have become a threat to game birds, fish and poultry as well as other wild indigenous species. This little chap above must not be confused with the European mink (which is not found in Britain) has a white spot on it's upper lip and is generally smaller and lighter....also the European mink is not as aggressive or adaptable as it's American cousin and seems to be on the decline. Because they can swim well, mink are able to raid islands which have been set up as sanctuaries for wild birds etc. Moreover, unlike most wild animals, they will kill even when they are not hungry...a bit like humans eh..!A bit of biology:

Size:

The male weighs about 1 kg (2.25 lbs) and he is about 24 inches in length. Farm bred males can reach 7 lbs.

The female weighs about 600g (1.25 lbs) and reaches a length of about 20 inches.

The sizes above do not include the tail which can be from 5 to 9 inches.Colour:

The minks rich glossy coat in it's wild state is brown, but farm bred mink can vary from white to almost black and this is reflected in the British wild mink. Their pelage is deep, rich brown, with or without white spots on the underparts, and consists of a dense, soft underfur overlaid with dark, glossy, almost stiff, guard hairs.Breeding season:

The breeding season last April to May.Gestation period:

Mink show the curious phenomenon of delayed implantation. Although the true gestation period is 39 days, the embryo may stop developing for a variable period, so that as long as 76 days may elapse before the litter arrives. Between 45 and 52 days is normally average.Litters/year:

There is only one (1) litter per year.Numbers/Litter:

This young lady has between 5 to 6 or 10 (depends on which source) cubs or kittens (depends where you are) per litter.Lifespan:

Their lifespan is relatively short in the wild, but some animals have been known to live for several years.Food preferences:

These chappies have a varied diet, they like: Fish, small mammals and birds (especially eels, rabbits and water fowl). Occasionally they dabble in crayfish.Predators:

Their main predator is man although otters have been known to kill mink.Distribution:

Mink are widespread in Britain's mainland, except in the mountainous regions of Scotland, Wales and the Lake District. They are also found in the Isles of Arran and Lewis. In Ireland they are less common.Waterside Habits:

Mink like to live near water and are seldom found far from riverbanks, lake and marshes. Even when roaming, they tend to follow streams and ditches. Sometimes they leave the water altogether for a few hundred metres, especially when looking for rabbits, one of their favourite foods. In some places, particularly in Scotland, they live along the seashore. Sometimes they even live right inside towns, if suitable water is available.

If you see something like a large weasel or small otter, near a lake or a river, or on the sea shore, it may well be a mink. Unlike the otter, which is only active at night when there is no danger of human disturbance, the mink is about at all hours, even when people are in evidence.

It is difficult to estimate the number of mink in Britain today. A mink needs several miles of waterside to make it's home and, considering the thousands of miles of waterways and courses throughout Britain, there must be thousands of mink in this country.Long, narrow territories:

Mink are very territorial animals. A male mink will not tolerate another male within it's territory, but appears to be less aggressive towards females. Generally, the territories of both male and female animals are separate, but a female's territory may sometimes overlap with that of a male. Very occasionally it may be totally within a male's.The territories, which tend to be long and narrow, stretch along river banks, or round the edges of lakes or marshes. Sizes vary, but they can be several miles long. Female territories are smaller than those of the male.

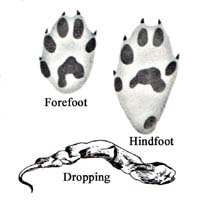

Each territory has one or two central areas (core areas) where the mink spends most of it's time. The core area is usually associated with a good food supply, such as a pool rich in fish, or a good rabbit warren. The mink may stay in it's core area, which can be quite small, for several days at a time, but it also makes excursions to the ends of it's territory. These excursions seem to be associated with the defence of the territory against any possible intruders. It is likely that the mink checks for any signs of a strange mink and leaves droppings (scats) redolent of its personal scent to reinforce it's territorial rights,(see sketch below for tracks and scats).

This shows mink footprints and a scat (dropping)

Toe marks do not always show up in the wildIn the territory, there are several dens. These may be in the roots or trunk of a water side tree, or among boulders (see picture below...this guy is hunting), or they may be temporary beds of dry grass or bracken. The mink may even use the abandoned nests of large birds, for it is an agile climber. Some mink seem to live temporarily without territories. These animals (called transients to differentiate between the territorial residents) are males which have left their territory to seek out females; young mink which have left their mothers and are looking for territories of their own to settle in; or animals which are seeking a better territory than the one which they have abandoned. (If a territory proves for any reason to be unsatisfactory - perhaps not rich enough in food - then the owner will abandon it and set of in search to find something better).

Mink are solitary animals for most of the year. Male mink avoid contact at all times, and seek out females only in the spring. Females have more contact with their own kind for, apart from meetings with the males for mating, they have the company of their offspring for a few months until they are old enough to go their own way.

Diet:

The mink eats anything big enough to be worth its attention and small enough to be caught and overcome. That means anything from about the size of a mouse up to the size of a rabbit. Although mink can swim well and catch many kinds of fish (showing a marked preference for eels), they are not so well adapted for aquatic hunter as the otter, and are not so dependant on fish for food. They eat more fish in the winter when the fish swim slower and are easier to catch. They are equally fond of furry prey and take mice, voles, rats, squirrels and young rabbits. If these are scarce, they turn to birds. As might be expected from an animal with such aquatic inclinations, the mink takes mainly waterfowl, particularly coots and moorhens.A serious pest:

Much is made of the mink's occasional raids on domestic stock and game, but studies have shown that the extent of these depredations is usually slight and of little importance countrywide, although no doubt infuriating to the farmer or gamekeeper who has suffered. Similarly, accusations have been made that mink have in some places exterminated such waterside creatures as moorhens and water voles. However, other places are known where flourishing populations of mink and voles or moorhens exist side by side, so the matter still rests in doubt.Social calls:

Male mink get the serious mating urge from February onward. They do not have permanent mates, so they leave their territories and travel the countryside in search of females. As explained above, mink show the curious phenomenon of delayed implantation. Although the true gestation is 39 days, the embryo may stop developing for a variable period. Usually the female has 5 to 6 or 10 young (depends on food sources, harbourage and security). The male does not help to rear the young and their feeding and training are entirely the responsibility of the female. The young remain with their mother until autumn, when they are fully grown. They then leave her to find territories of their own. It seems likely that there is a considerable rate of failure in this move to independence, and the first year mortality, due to starvation, is high.